[ad_1]

This story is part of Plugged In, CNET’s hub for all things EV and the future of electrified mobility. From vehicle reviews to helpful hints and the latest industry news, we’ve got you covered.

At a time when it costs up to $100 to fill a gas tank, but as little as $10 to charge an electric car, buying an EV may seem like an obvious choice. But EV economics are complicated and you need to be savvy about a lot of unfamiliar factors before you can stick it to the oil companies.

Buying a new car

To drive an EV you have to buy an EV, an often pricey proposition. Even after you sell or trade your current, conventional car you could easily be in the hole $10,000 or more. It’ll take you several years to just break even, as my CNET Cars colleague Craig Cole calculates here, even assuming a scenario where you buy a very cheap EV, live in a place with cheap electricity and always charge at home. That’s a lot of “ifs” to make the purchase of a new EV an economic slam dunk.

This is not a new concern: I can’t count the number of people I know who bought a hybrid or other fuel-efficient car at a net cost far higher than they could ever save on fuel with it. One friend insisted on trading in their Porsche Cayenne for a Cayenne Hybrid, even after I penciled out that it would take them 111 years to break even.

It’s set the electric car market on fire, but a Tesla Model 3 starts at $47,000, a full $10,000 more than just a year ago. Average transaction prices are closer to $60,000.

Tim Stevens/CNET

To be sure, a pure electric car will save you far more on energy than that Cayenne Hybrid example, but an EV’s initial purchase price and potentially higher insurance and elevated repair costs can blunt its economics. On the other hand, conventional cars have a litany of maintenance costs that EVs don’t incur, like fluid changes and more frequent brake service.

A lot of people buy an EV to save the environment as well as money, a noble motivation that returns their investment via both fuel savings and environmental dividends. It’s beyond the scope of this article, but think about overall environmental ROI and ask yourself if there’s a more effective way to deploy the net funds you’d spend on an electric car: Installing rooftop solar or building out a top-notch Zoom room to cut out most of your business air travel are a couple of examples that can be considered using a good carbon-footprint calculator.

Steep depreciation

Depreciation is the “other price” of any car you buy and even more important to consider when that car is electric. The value of any new or late model car drops like a stone as you own it, creating a substantial cost every mile that is often worse for EVs due to their typically higher price and often greater depreciation.

For example, Subaru, which is not known for electrified cars, has an average resale value that is 66% of its new price after five years, according to Car Edge. On a new $35,000 Subaru, that depreciation would cost about $11,500 over the first five years, or $6.30 a day. To use an overworn metaphor, that’s a latte for you and a friend, seven days a week.

Compare that to a Tesla, which Car Edge projects will hold 58% of its value after five years (which puts it No. 3 among luxury brands, according to Car Edge), and does so from a higher average price. If you buy a $60,000 Tesla Model 3 you’ll incur $25,000 in depreciation over the first five years, or $13.80 a day — like buying you and three friends a latte every single day. Part of the pain is due to the fact that Tesla has been so successful at selling EVs that its cars long ago ceased to qualify for a $7,500 federal tax credit.

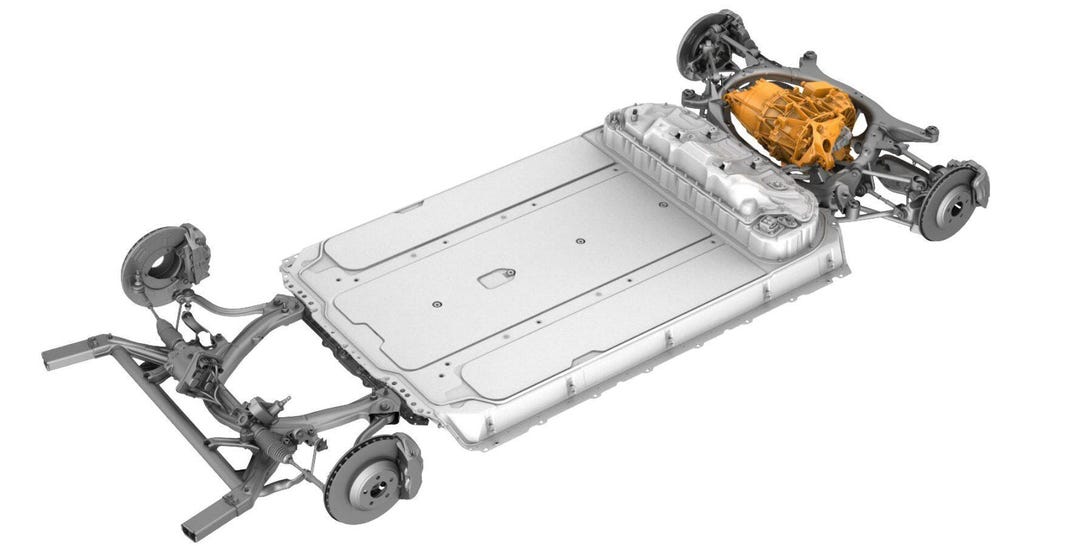

The heart of an EV is its battery pack, analogous to the central value of an engine in a conventional car. Unlike modern car engines, EV batteries present the prospect of replacement during the vehicle’s service life.

Tesla

Battery replacement

An important form of depreciation that is unique to EVs is eventual battery pack replacement. Unlike a modern conventional car where an engine replacement is unlikely, replacement of an EV’s battery park is likely as the vehicle ages and delivers unsatisfactory range. Battery replacement cost is highly variable, but $10,000 is a fair median estimate.

That said, this cost remains hazy because few EVs have been on the road long enough to highly degrade their battery pack, nor has there been enough time for a vibrant, competitive battery-replacement market to develop. It’s also hard to predict which owner of a given EV will shoulder the battery-replacement cost and, while this cost should already be factored into depreciation, I’m not sure the market is mature enough yet to count on that. If you buy a late model used EV know that you may be the one holding the bag when its range drops to a level that either you or the next buyer may consider insufficient, triggering an expense or loss of value that erodes the overall economy of driving electric.

That said, there’s a good workaround to this battery-replacement concern: reality. See my take on why you may not need anywhere near the range you think you do.

Buying electricity isn’t simple

The cost of electricity varies far more than the cost of gasoline, depending on where you live, the rate plan you’re on, when you charge, and whether you do so at home or at a commercial public charger.

In California we pay an average of 18 cents per kilowatt hour for residential electricity, but in Idaho it’s 8 cents and in Hawaii it’s 28 cents, according to the US Energy Information Administration. That variance would be like paying $5 a gallon for gasoline in California, $2.50 a gallon in Idaho and $8 a gallon in Hawaii, wildly greater variation than we see at the pump. And the cost of electricity isn’t clearly labeled where you dispense it, buried instead in a morass of tariffs and times of day.

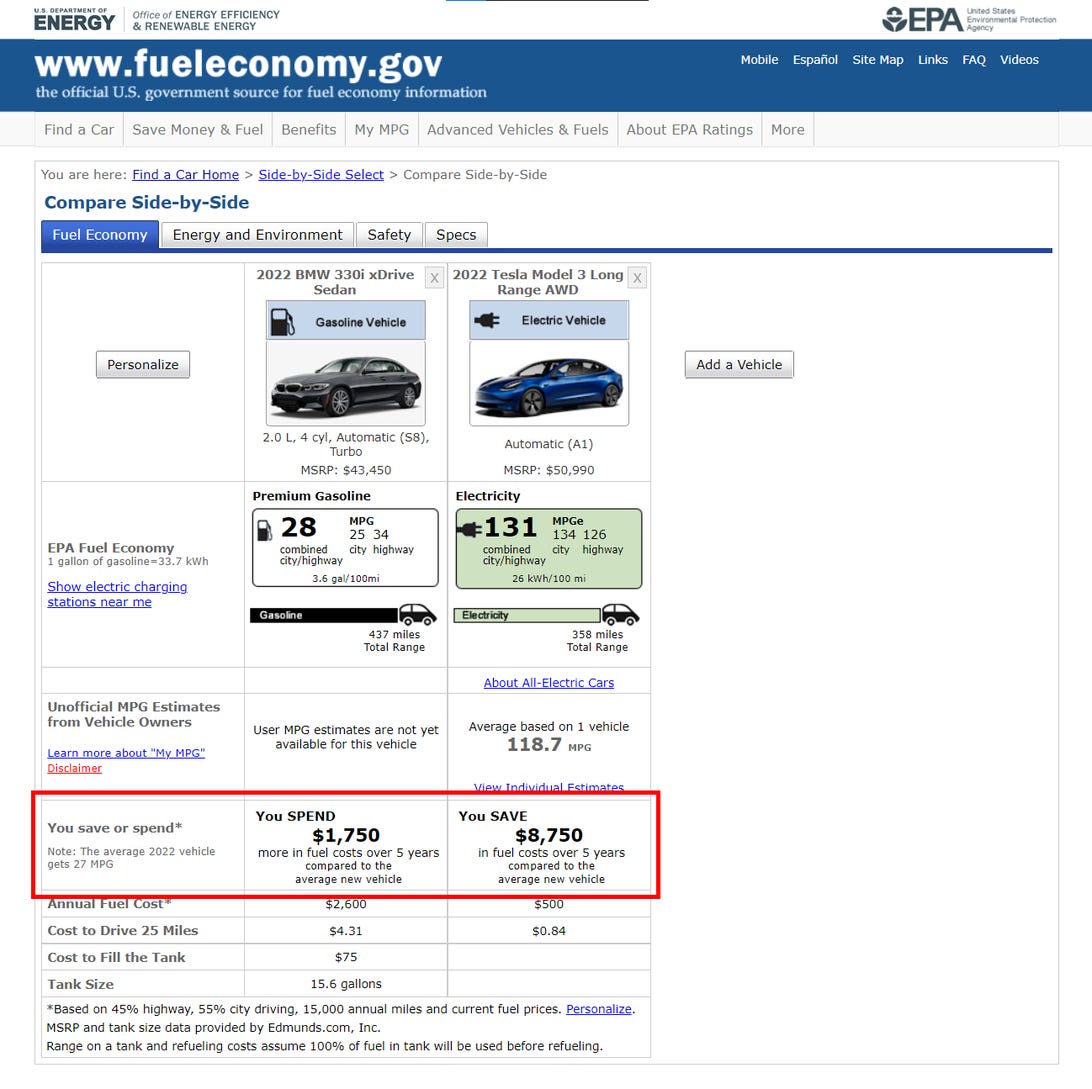

You can turn to the Environmental Protection Agency’s Fueleconomy.gov for a cost comparison between cars, gas or electric. A head-to-head comparison between a BMW 330i xDrive and a Tesla Model 3 Long Range lays out a stark difference in energy costs that makes the Tesla seem like an absolute cost-saving machine.

If only it were this simple.

EPA/Screenshot by Brian Cooley/CNET

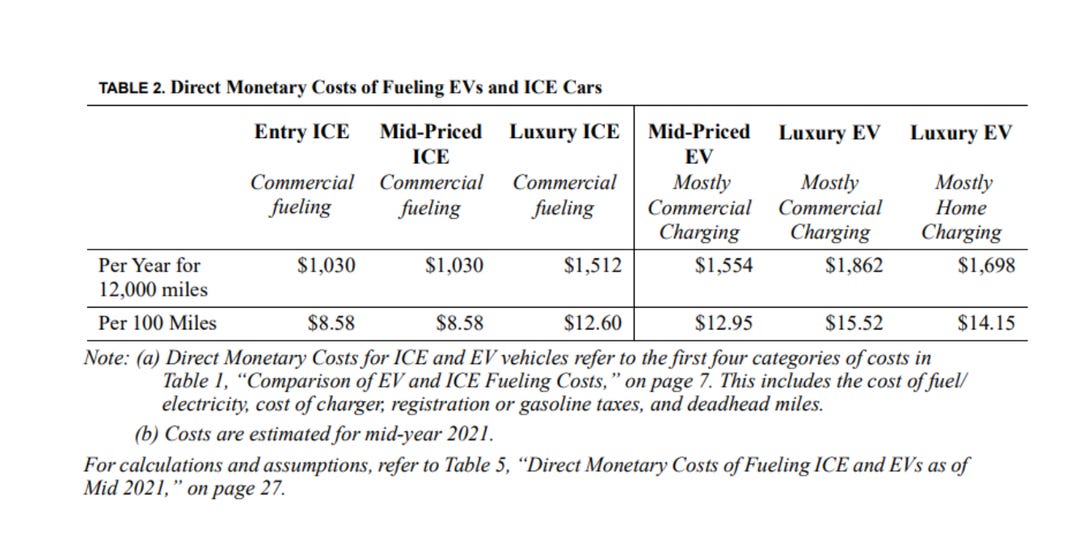

But a 2021 study by Anderson Economic Group (PDF) concludes that driving an EV can cost substantially more than driving a conventional vehicle. It’s a controversial conclusion, but not entirely unfounded, although its assumptions include a lot of charging at commercial locations, rather than at home, and that you make a healthy salary that needs to be accounted for as wasted value while you wait for your car to charge. For those who charge at home the story is much rosier, but Anderson wisely amortizes the roughly $2,000 cost of a Level 2 charger, which most EV owners will want.

A worst-case take on owning an EV can result in figures that show it costs more than a gas-engined car.

Anderson Research Group

To answer the question we started with, it either costs less, the same or more to operate an EV compared to a gas-engined car. While that’s not a very satisfying answer, an EV will probably reduce your true cost of getting around, albeit maybe not overnight. I think a shift to EVs is inevitable for a variety of technological, political and financial reasons, but you need to worry about how EVs pencil out for you, not for us.

[ad_2]

Source link