[ad_1]

With the Synology RT6600ax and Asus GT-AX11000 Pro being close to their releases, you might have many questions about the 5.9GHz Wi-Fi 6 band, that “final frontier” of the standard, or more precisely, of the 5GHz spectrum.

Or you might have never heard of it and are wondering what I’m talking about.

In either case, you’re reading the right post. I’ll explain what 5.9GHz Wi-Fi is and set some realistic expectations regarding its hardware.

Things are still not super clear right now, but, like usual, I’ll update this post as I find out more via real-world, hands-on testing when that’s possible.

So, what is the 5.9GHz Wi-Fi 6 band anyway?

Wi-Fi first started with the 2.4GHz frequency band, and with the original move from single band to dual-band back in 2009, we have since also had the 5GHz band.

As you might have noted, 2.4(GHz) is just a portion between 2 and 3 while 5(GHz) is a whole number. It’s supposed to be the entire band.

Or is it?

The initial three UNII groups

In reality, Wi-Fi also doesn’t have the entire 5GHz band for itself — far from it. And this band also has a lot of smaller portions starting with 5.1GHz all the way to 5.9GHz.

You can visualize Wi-Fi airspace by putting a measuring tape on a floor. Before it hits that 6-meter mark, the surface has to encompass the entire 5-meter section, which includes many little sub-sections, called millimeters.

Substitute “meter” with “foot” and “millimeter” with “inch” if you use the inch-pound system. The units are different in values, but the idea remains the same for this post.

In fact, the sub-portions are so small they are often conveyed in MHz — 1GHz = 1000MHz. And for better management, in the US, these are divided into four frequency range groups, not-so-aptly called Unlicensed National Information Infrastructure or UNII.

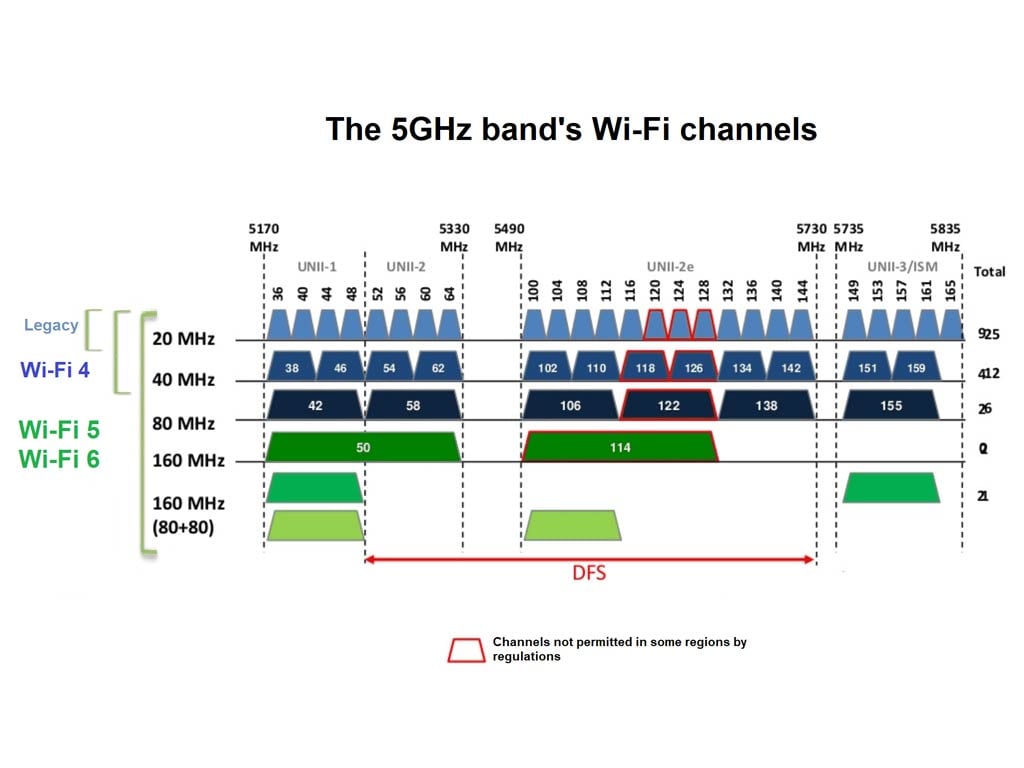

For Wi-Fi-related applications, the following are the ballpark breakdown of these groups — the MHz values are rounded:

- UNII-1 ranges from 5170MHz to 5250MHz

- UNII-2: 5250MHz to 5330MHz

- UNII-2e (extended): 5490MHz to 5730MHz

- UNII-3: 5735MHz to 5835MHz

- UNII-4: 5850MHz to 5925MHz

Note: The grouping is relatively flexible. For example, depending on who you’re talking to, the UNII-2e can be considered part of UNII-3.

You will note that there are gaps in the spectrum between these groups. Those are areas of spectrum permanently dedicated to non-Wi-Fi applications. The gap between 5330MH and 5490MHz, for example, is used for Doppler RADAR at all times.

On top of that, both UNII-2 and UNII2e are part of the Dynamic Frequency Selection (DFS) shared between other RADAR applications and Wi-Fi, with the former always having the priority.

The chart above shows how the first three U-NII groups apply to 5GHz Wi-Fi, and the channels end at the 5835MHz mark. Up to late 2021, only UNII-1, UNII-2/e, and UNII-3 were available to Wi-Fi.

And that brings us to the fourth UNII group, which includes the 5.9GHz portion.

The controversial UNII-4 spectrum

To understand the significance of the 5.9GHz band, we first need to know how Wi-Fi works in terms of speed.

In a nutshell, the smallest portions of the airspace, called channels, are 20MHz wide. But you can add contingent ones together to increase the width and, therefore, the bandwidth. So two 20MHz channels make a 40MHz one, and two 40MHz create an 80MHz channel.

Back to the measuring tape analogy, you can combine multiple millimeters into a centimeter and multiple centimeters into a decimeter.

Essentially, it’s as basic as putting adjacent sections of a surface together to create a large single continuous area.

Wi-Fi 6 is the first standard that supports the 160MHz channel width. I wrote about the standard in great detail in this post, but the gist is:

- Wi-Fi 6 needs 160MHz channel width to deliver top performance.

- Since 160MHz is wide, within the first three UNII groups, there is enough space for only two 160MHz channels.

- Both of these 160MHz channels encompass DFS air space. As a result, the router might have a brief disconnection when RADAR signals are present. To avoid that, many Wi-Fi 6 broadcasters (routers, access points) might not use the 160MHz channel width and opt for the narrower but more reliable 80MHz, which cut the standard’s ceiling speed in half.

And that brings us to the UNII4 portion of the 5GHz band, often referred to as the 5.9GHz band.

For decades, this portion has been controversial because it was reserved for the auto industry, which has never used it — it’s a long story.

Wi-Fi advocates fought long and hard for this final airspace of the 5GHz band, and, finally, in late 2020, FCC approved it for Wi-Fi use and then made it available for hardware vendors in late 2021.

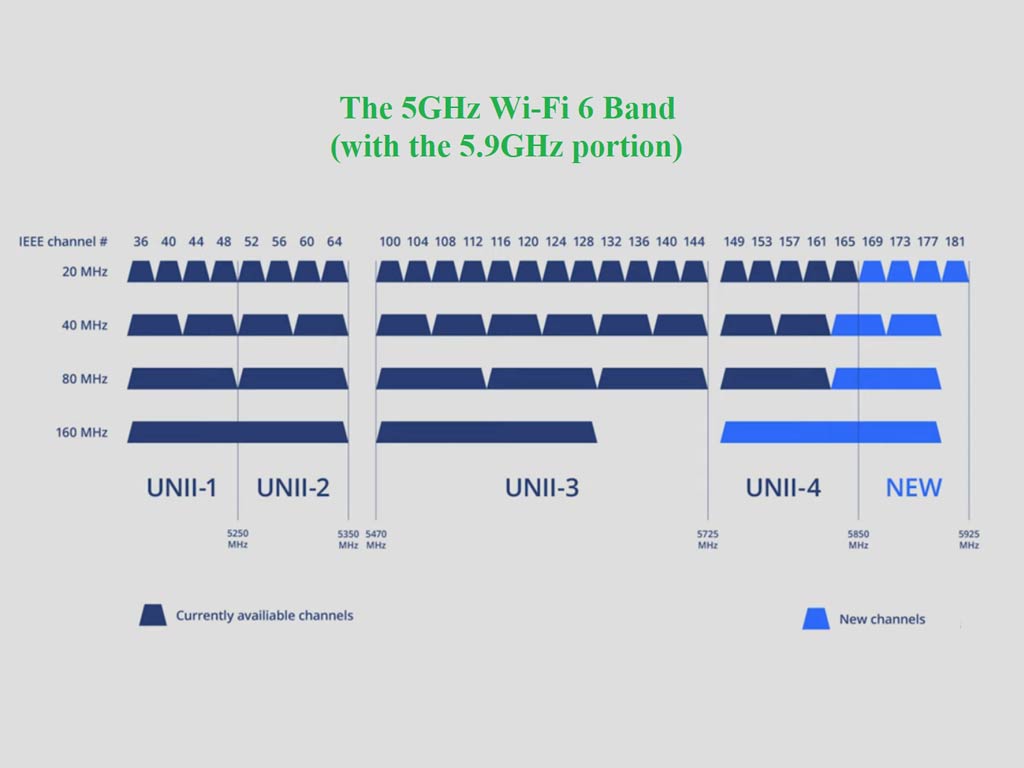

The table above shows how the addition of the UNII-4 group completes the 5GHz band for Wi-Fi use. Specifically, it extends the band’s tail with four more 20MHz channels, more than enough to create the third 160MHz channel on this band.

Most importantly, it’s the only 5GHz 160MHz channel that does not use DFS. In other words, it’s the only “clean” channel that can deliver Wi-Fi 6’s top speed and reliability, even when used near RADAR stations.

You might have heard of Wi-Fi 6E with the all new 6GHz band that has enough space for seven clean 160MHz channels. However, this band has proved in my testing to have a much shorter range than 5GHz.

That said, the 5.9GHz might have the best of both worlds: Fast Wi-Fi 6 speeds (up to 4800Mbps in the current top 4×4 specs) and the long-range.

And that’s how this new portion can be exciting. Still, we’ll have to wait and see how it pans out in real life. And that brings us to the endearing questions relating to hardware.

5.9GHz Wi-Fi 6 band’s hardware: Will UNII-4 work with existing equipment?

When it comes to hardware, the first question is, will existing Wi-Fi 6 broadcasters (routers and access points) support the new 5.9GHz (the UNII-4 portion) via firmware update?

On the broadcasting side: It’s a no

I’ve asked multiple hardware vendors this question, and the answer is no.

To sell a Wi-Fi product, in the US at least, hardware vendors need to get it certified by the government. All existing Wi-Fi 6 broadcasters are not approved for the UNII-4 portion of the band which was not available during their certifications. And there are no benefits, both in time and cost, for the vendor to get them re-certified.

Consequently, if you want to use the new cool 5.9GHz band, you will need to get new hardware on the broadcasting side. The Asus GT-AX11000 Pro and the Synology RT6600AX will be the first routers supporting UNII-4. Both are slated to be available in 2022.

On the client side: It’s a maybe

On the receiving end, the question is will existing Wi-Fi clients support the 5.9GHz band vis driver update? On this front, the answer is it depends.

While the certification is less restrictive on the client-side, we only know if this works when the broadcasters are available.

So chances are some of the existing Wi-Fi 6 adapters, such as the Intel AX2xx, will get new driver software to support the 5.9GHz portion. Again, that’s a maybe.

5.9GHz band: The takeaway

The availability of the 5.9GHz band for Wi-Fi use is a natural progression — this UNII-4 portion should have been open to Wi-Fi years ago. But better late than never, and the final frontier of Wi-Fi 6 is exciting.

However, everything takes time. You might have noted that Intel hasn’t even released the official driver for its AX210 Wi-Fi 6E chip to support the 6GHz band on Windows 10 — you have to use Windows 11.

So, one thing is sure: there will be a long window when you can get a UNII-4-ready router without any supporting client. But the router will work with all existing clients using existing portions of the spectrum anyway.

But I guess by the end of 2022 or earlier 2023, the use of the 5.9GHz band will be relatively ubiquitous. Just don’t quote me on it.

[ad_2]

Source link