[ad_1]

This post is part of the series designed for anyone who wants to build a home network from scratch, including those who consider themselves uninitiated.

That said, if you’re new to home networking, this is a good place to start. And if you have set up a router before, this piece can be a good refresher. In any case, the related posts in the box below will help with other home networking questions.

By the way, this is a long read. Returned users will find the Table of Content below handy.

Dong’s note: I originally published part of this post on February 15, 2018, and updated it on March 21, 2022, with a great deal of additional up-to-date and relevant information based on readers’ questions and requests.

Home network basics: It’s wired vs Wi-Fi

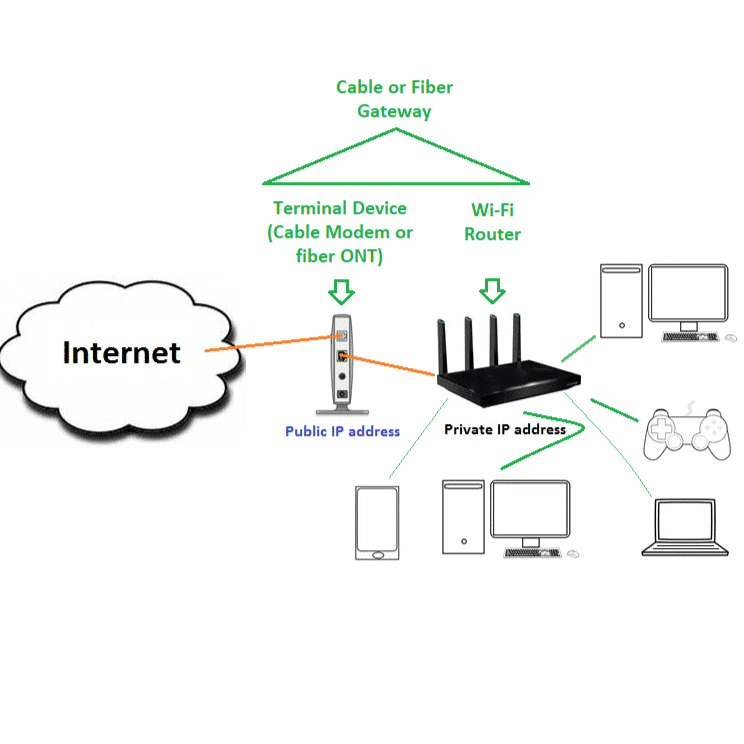

A home Wi-Fi network includes wired and Wi-Fi parts.

While Wi-Fi requires a bit of imagination, we can easily see the former — it’s the hardware itself. And in any network, we tend to see the following common parts that you might or might not have heard of:

- A Wi-Fi router: This is the heart of your home network.

- A terminal device: This is the Internet source is represented by a Cable Modem (for Cable broadband), an ONT (for Fiberoptic broadband), or a cellular modem (4G or 5G broadband.)

- A gateway: A combo device that includes #1 and #2 in a single box.

- A switch: A device that adds more ports to the router.

- Wi-Fi exenders, access points or mesh satellites: The addtional hardware that extend a Wi-Fi network.

Not all networks have all items above. In fact, many home networks likely include either item #1 and #2 or #3.

But all of them have two things in common, the network cable and ports. You can’t run away from those. So, let’s start with them.

Home Wi-Fi Network hardware: Ports and cables

A network port is a hole that you can plug a network cable into — the two just fit.

Physically, these ports all look the same, but they can be different in what they do and in their speed grades. And that brings us to the widely used BASE-T port standard.

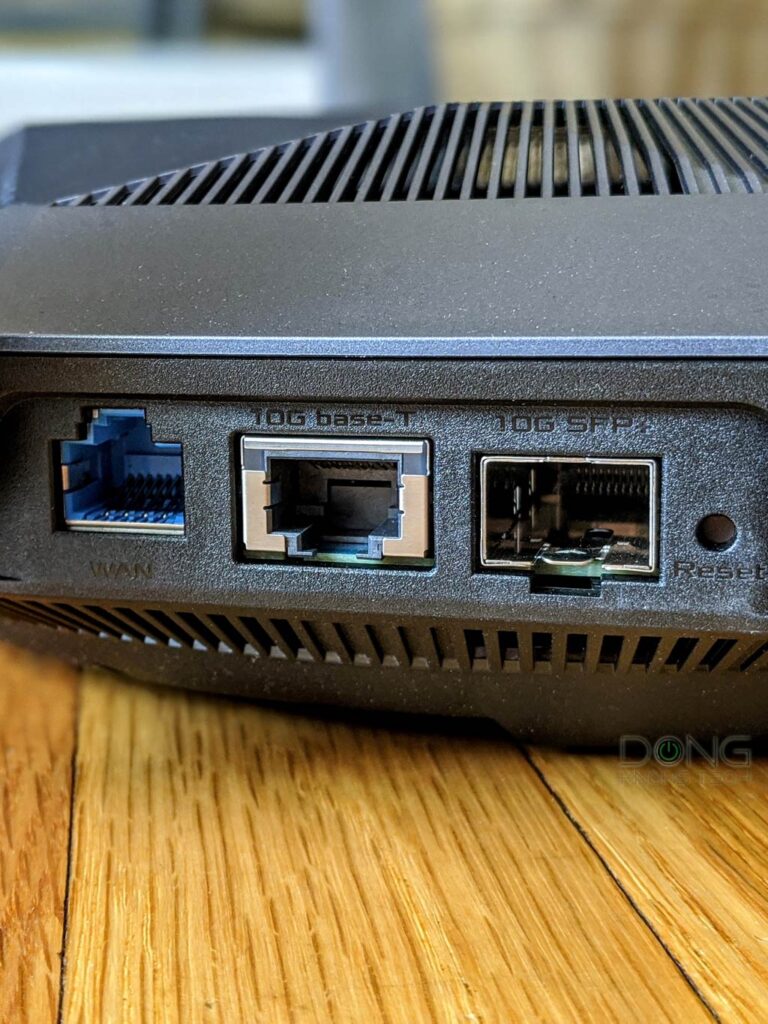

BASE-T vs SFP+

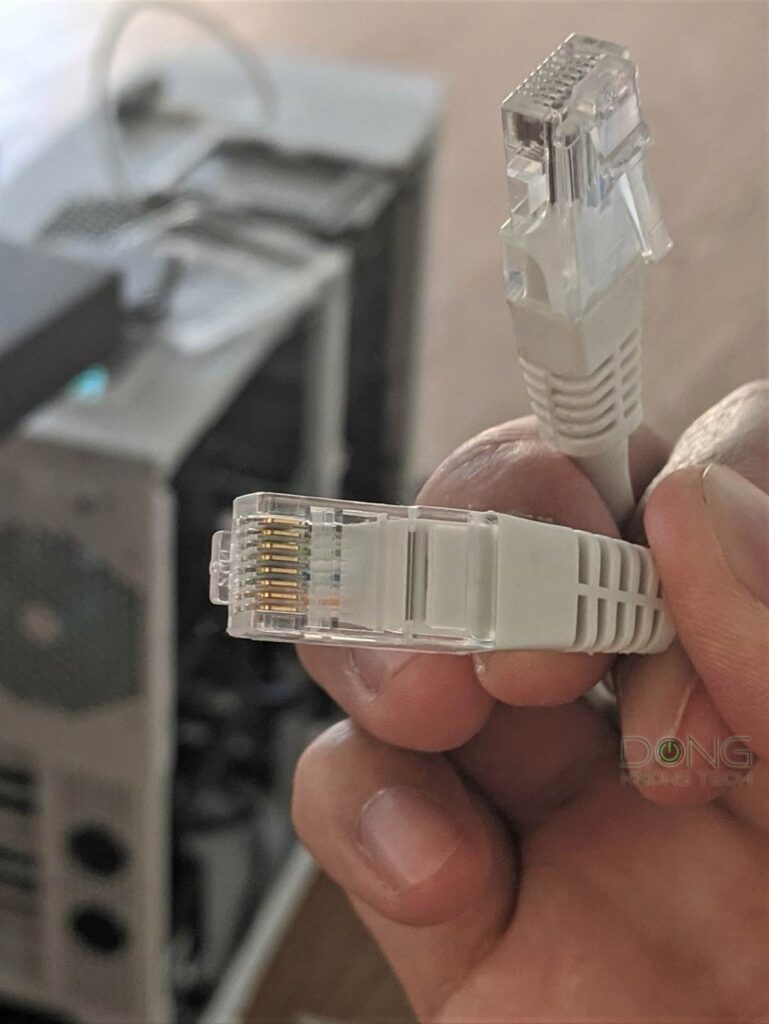

The BASE-T (or BaseT) port type refers to the wiring method used inside the network cable and the connectors at its ends, which is 8-position 8-contact (8P8C). This type is known via a misnomer called Registered Jack 45 or RJ45. So we’ll keep calling it RJ45.

But there’s also SFP or SFP+ (plus) port type, used mostly for enterprise applications, that’s different physically but has the same networking principles as Base-T. SFP stands for small form pluggable and is the technical name for what is often referred to as Fiber Channel or Fiber.

An SFP+ port has the speed grades of either 1Gbps or 10Gbps — the older version SFP can only do 1Gbps. The two share the same port type. That’s all you need to know about SFP. Base-T is the more popular by far.

Generally, you can get an adapter to use a BaseT device with an SFP or SFP+ port. Still, in this case, compatibility can be an issue — a particular adapter might only work (well) with the SFP/+ port of certain hardware vendors.

Generally, you’ll find network ports on the back of a router — more below. Looking closely, you’ll note that all routers have two types of RJ45 ports labeled as WAN (or Internet) and LAN.

Most routers include one WAN port and a few LAN ports. The WAN port tends to have a different color or is separate from the LANs for easy recognition. So what do they do?

WAN port

WAN stands for wide area network, which is a fancy name for the Internet. You use the port to hook the router to an Internet terminal device, like a modem. (More on modems below.)

LAN port

LAN stands for local area network. It’s generally a port type that hosts local devices.

Specifically, you use them to connect wired devices, like a desktop computer, a printer, or a game console, to your home network. Devices connected to a router are part of a local network — they can “see” and “talk” to one another.

A router tends to have more than one LAN port. When they run out, you can add more using a network switch. But before that, let’s find out a few extra things you can do with the network ports.

Extra: Dual-WAN and Link Aggregation

Some routers can support two Internet sources, like when you have Cable and Fiberoptic and want to use them simultaneously. That’s a Dual-WAN setup.

In this case, it can have two WAN ports (or it can turn one of its LAN ports into a WAN) or use a USB port as the second WAN to host a cellular dongle.

A Dual-WAN setup increases your network’s chance to remain online during outages (failover), or you can combine the two Internet sources to get better broadband speeds (load-balance).

Link Aggregation, also known as bonding, is where multiple network ports of a router aggregate into a single fast combined connection. Typically, you can have two Gigabit ports working in tandem to provide a 2 Gbps connection.

Many routers from known networking vendors have this feature. You can have Link Aggregation in WAN (Internet) or LAN sides. The former requires a supported modem — again, more on modem below). And in the latter, your wired client also needs to support it. Most NAS servers do.

Link Aggregation is also available in the failover or load-balance configuration.

Network switch

A switch is a device that adds LAN ports to a local network. In many ways, you can understand the LAN ports on a router as part of the router’s built-in switch.

Connect one of a switch’s ports to a router, and now the rest of its ports will work just like those on the router.

So, a switch always loses one of its ports to connect itself to an existing network. That said, you want to get one that has the same number of ports as the wired devices you wish to add to the network, plus one. Or just get a switch with plenty of ports to spare.

Generally, switches differentiate between themselves by the number of ports and their ports’ speeds — more below. And then, there are PoE, unmanaged, and managed switches in case you’re interested in finding out.

You’ll note what type of switch one is via its name. For example, the Zyxel XS1930-12HP is a 12-Port Multi-Gig PoE Managed switch.

So what is a un/managed switch?

Unmanaged switch

An unmanaged switch adds more ports to a router, and that’s it. Plug it in, and you’re good to go. All of its ports work equally.

This type of switch is a perfect fit in a home or even an office. In this case, you just need to get one with the number of ports (the more, the better) and the speed (the faster, the better) needed.

Managed switch

On the other hand, a managed switch comes with additional networking features, such as VLAN, traffic prioritization, filtering, virtual network, and many more. In other words, you can make the ports do different things.

The more the switch can do, the more expensive it gets — as expensive as tens of thousands of dollars. And you will need to configure these features manually.

For this reason, generally, only big businesses would need this type of switch. In a home, the router is your managed switch. (You can understand a home router is a combo box of a managed switch plus the routing function.)

That said, getting a managed switch for your home can cause issues if you don’t know what you’re doing.

By default, most managed switches work in the unmanaged mode out of the box — so there might be no real issue in using one. But that is not a sure thing, and in this case, the extra cost might still be unnecessary.

PoE switch

PoE, or Power-over-Ethernet, is a feature where a switch’s port can power a PoE device via the same network cable. You can find both managed and unmanaged switches with PoE capability.

Again, it’s always good to get a fast PoE switch. However, if your PoE device does not require high speed, such as an IP camera, then a slow (Fast Ethernet) PoE switch will do.

Common network port speeds: Fast Ethernet vs Gigabit vs Multi-Gig

You might have heard of Gigabit. Currently, that’s the most popular network standard speed grade.

Speed grade, by the way, is generally used to classify a device. So, for example, a switch with Gigabit ports is known as a Gigabit switch.

But other than Gigabit, we also have two more speed popular grades, including Fast Ethernet and Multi-Gig. Let’s start with Fast Ethernet.

Fast Ethernet

Despite the name, Fast Ethernet is actually not that fast. It caps at only 100 megabits per second (100Mbps) — that’s one-tenth of the Gigabit speed.

Fast Ethernet has another slower mode that’s only 10Mbps. For the most part, Fast Ethernet is slowly fading away, with most new computers and devices supporting Gigabit as the minimum.

But 100Mbps is not that slow, either. To put things in perspective, generally, a character — that’s a letter or a blank space between two words you see on the screen — needs eight bits (or a byte). So 100Mbps means you can deliver 12,500 letters per second.

The text on this page you’re reading is made of some 25,000 characters and would require less than two seconds to transmit via Fast Ethernet.

By the way, that 100Mbps is more than fast enough for most streaming services. For this reason, many new streamers, such as the Xfinity Flex, still use a network port of this speed grade.

Gigabit

Again, gigabit is the most popular wired networking standard right now. A Gigabit connection can deliver 1 gigabit per second (Gbps) — that’s 1000 megabits per second (Mbps), or 125 megabytes per second (MB/s).

At this rate, you can transmit a CD worth of data (some 700MB) in about 6 seconds. Pretty fast.

Multi-Gig

It’s called Multi-Gig because it can handle multiple gigabits at a time. There are three Multi-Gig grades, including 2.5Gbps, 5Gbps, and 10Gbps.

The term “Multi-Gig” generally refers to a new standard that uses existing Gigabit wiring to deliver faster-than-Gigabit speeds with full backward compatibility.

For example, a 5Gbps Multi-Gig port can also work at 2.5Gbp, 1Gbps, or even 100Mbps, but it can’t connect at 10Gbps or slower non-grade speeds like 3Gbps or 1.5Gbps. Like all connections, the actual real-world rate will vary.

So, does a Multi-Gig port work with a Gigabit port? Let’s find out.

Network cable and port grades

All BASE-T network ports share the same port type. The port itself can host any RJ45 network cable, but the speed will be that of the cable or port grade, be it Gigabit, Multi-Gig, or Fast Ethernet, whichever is the slowest.

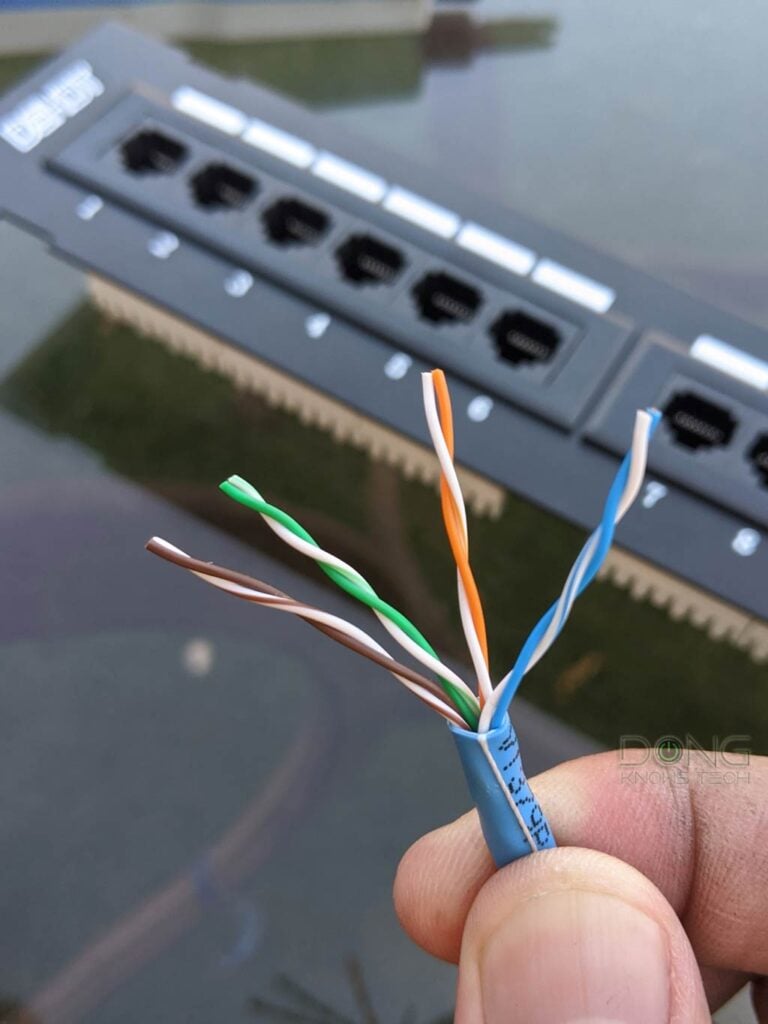

Network cables and ports also have different with different grades. The most popular is CAT5e, but you’ll also find CAT6a, CAT 7, etc. No matter which one you use, the physical wiring inside the cable remains the same — it’s the wires themselves that are different and decide how fast a cable/port can be.

That said, you can plug a CAT7 cable into a CAT5e port, and they will work together. The speed, however, will be that of the lower standard. So how fast are they?

You can generally expect any BASE-T network cable (and port) to deliver 1Gbps (Gigabit) to up to 100 meters (328 feet) in length.

So, if you need to expand your network farther than 300 feet away, consider putting an active device — like a switch — in between. If not, expect the speed to degrade.

All cable types mentioned above can also handle Multi-Gig — that’s up to 10Gbps — and they all work interchangeably.

Here’s the distance (length) in which each type of network cable can deliver up to 10Gbps:

- CAT5e: 45 meters (148 feet)

- CAT6: 55 meters (180 feet)

- CAT6a: 100 meters

- CAT7: Over 100 meters. (CAT7 can deliver speeds faster than 10Gbps.)

So, for virtually all homes, the popular CAT5e cable will suffice. But it doesn’t hurt to run higher-grade (and more expensive) cables.

By the way, CAT5e is generally the lowest Gigabit-capable wiring grade. A cable of a lower grade than CAT5e normally can only deliver Fast Ethernet. In other words, in this case, re-wiring is required if you want faster speeds.

For more on running network cables, check out this post on DIY network wiring.

The final speed of a mixed standard setup

While you’ll have no problem plugging network cables of different grades into any port grade, keep in mind that the connection speed is always that of the slowest party involved.

Like real-life traffic, a bottleneck device will impede the final flow rate. Specifically, if you use a CAT5e cable with CAT6 ports, the connection is now of CAT5e-grade.

Another example is when you plug a (1) Fast Ethernet device, a (2) Gigabit device, and a (3) Multi-Gig device into a Gigabit switch, the link speeds between them at any given time will be the following:

- Between 1 and 2: 100 Mbps (the fast Ethernet device is the bottleneck)

- Between 1 and 3: 100 Mbps (the fast Ethernet device is the bottleneck)

- Between 2 and 3: 1 Gbps (The Gigabit equipment is the bottleneck)

This final speed rule applies to all network connections, both wired and wireless.

With ports and cable out of the way, let’s find out about the actual hardware pieces of a home network.

Modem vs Router vs Gateway

As mentioned at the beginning, chances are you’ll run into a modem, a router, or a gateway in a home network. Folks tend to call these three arbitrarily or interchangeably, but they are distinctive hardware pieces.

What is a modem?

First of all, the modem is just one of many service-specific terminal devices. If you use DSL or Cable for your broadband, you’d need a modem. But if you use Fiberoptic, then you’d need an ONT.

Considering that Cable Broadband has been widely used, you more likely run into a modem.

That said, the word actually is MoDem. It’s an acronym for a device that works both as a modulator and a demodulator. A modem converts computer data signals into those of the service line and vice versa.

It’s fairly easy to identify a modem. It’s a device that always has one service port to connect to the service line, that comes into your home from the utility pole outside and one network port. This network port is where you connect to the router’s WAN port, as mentioned above.

Some cable modems also have a phone jack for phone service, and others might have an additional network port for WAN Link Aggregation, as mentioned above.

But generally, when you see a service port on a device, it has a modem on the inside. Also, check the label; you might find the word “Modem” on it.

Generally, a modem can bring the Internet to just one wired device connected to its LAN port. Since we sure have more than one device at home, we need a router.

What is a router?

Every home network must have one router — and preferably no more. A router always has one WAN (Internet) port to connect to the Internet source.

Generally, you can use a router with any Internet source — any terminal device, an ONT, or a modem — as long as the source has a network port.

On top of that, a router also has a few (usually four) LAN ports for wired devices. Most, if not all, home routers also have a built-in Wi-Fi access point — it’s a Wi-Fi router.

As for how to identify, a Wi-Fi router tends to have a few antennas, though some might have internal ones. But generally, if you look at its label, you’ll see the word “router” on it.

The job of a router is to create a network that allows multiple devices to talk to one another locally. On top of that, it also shares the single broadband connection of the Internet source (the modem) to the entire network.

Physically, a router does this via its LAN ports or built-in Wi-Fi access point — more on Wi-Fi below. Internally, the router’s NAT and DHCP functions take care of the sharing, which I explained more in this post on IP addresses.

A router + Internet receiver (modem) = A gateway

A gateway, or residential gateway, is just a combo device that includes a router and an Internet terminal device (often a modem, but can also be an ONT for certain Fiberoptic services) in a single hardware box.

That said, a gateway will generally have a service port plus a few (usually four) LAN ports. It tends not to have a WAN port.

If you use equipment provided by a Cable service provider, chances are it’s a gateway. In this case, the company technician might call it a “modem,” which, though partly true, contributes to the confusion.

You can also buy a retail gateway. The Netgear Orbi CBK752 is an example — it’s a cable gateway. Considering nobody bothers to use the correct terminology, Netgear actually calls it a Cable Modem Router.

Now that we’ve gone through the visible hardware part of a network, let’s find out about the invisible part, the Wi-Fi.

Understanding Wi-Fi: Distance vs signal strength

The only thing you can see about your Wi-Fi network is the antennas, and that’s only true when you don’t have a router with internal ones. On a mobile device, that’s almost always the case — the antennas are blended in with the device’s chassis.

And then what happens in between those antennas are pure mysteries.

How Wi-Fi works

The details of Wi-Fi can be overwhelming — more about that in this post about different Wi-Fi standards.

But all standards, including the latest Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 6E, share this same principle of radio broadcasting:

You have a broadcaster (your router) that emanates radio signals outward and a receiver (your laptop) that catches those signals, using a Wi-Fi adapter to form an invisible link that can transmit data between the two. One broadcaster can handle multiple receivers at a time.

(That is when we use the most popular mode of Wi-Fi, called infrastructure. There’s another mode, ad-hoc, where you can connect two Wi-Fi receivers directly to each other. But that’s a bit too much technical detail.)

That said, Wi-Fi is a wireless alternative to network cables. In other words, when a device connects to a router using Wi-Fi, it uses an invisible network cable. The length of this “cable” is the router’s Wi-Fi range.

I’ve gotten many questions about the range of Wi-Fi routers. If you have those, click the button below to find out more.

Extra: Wi-Fi range in theory vs real world

Note: This portion of extra content was first published in the post on Wi-Fi standards.

Wi-Fi range in theory

The way radio wave works, a broadcaster emits signals outward as a sphere around itself.

The lower the frequency, the longer the wave can travel. AM and FM radios use frequency measured in Megahertz — you can listen to the same station in a vast area, like an entire region or a city.

Wi-Fi uses 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, 6GHz frequencies — all are incredibly high. As a result, they have much shorter ranges compared to radios. That’s not to mention a home Wi-Fi broadcaster has limited power.

But these bands have the following in common: The higher frequencies (in Hz), the higher the bandwidth (speeds), and the shorter the ranges. It’s impossible to accurately determine the actual range of each because it fluctuates a great deal and depends heavily on the environment.

That said, below are my range estimates of home Wi-Fi broadcasters, via personal experiences, in the best-case scenario, i.e., open outdoor space on a sunny day.

Note: Wi-Fi ranges don’t die abruptly. They degrade gradually as you get farther away from the broadcaster. The distances mentioned below are when a client still has a signal strong enough for a meaningful connection.

- 2.4GHz: This band has the best range, up to 175ft (55m). However, this is the most popular band, which is also used by non-Wi-Fi devices like cordless phones or TV remotes. Its real-world speeds suffer severely from interference and other things. As a result, this band now works mostly as a backup, where the range is more important than speed.

- 5GHz: This band has much faster speeds than the 2.4GHz band but shorter ranges that max out at around 150 ft (46 m).

- 6GHz: This is the latest band, available with Wi-Fi 6E. It has the same ceiling speed as the 5GHz band but with less interference and overheads. As a result, its actual real-world speed is faster. In return, due to the higher frequency, it has just about 70% of the range, which maxes out at about 115ft (35 m).

Some might consider these numbers generous, others will argue their router can do more, but you can use them as the base to calculate the coverage for your situation.

Wi-Fi range in real-life

In real-world usage, chances are your router’s Wi-Fi range is a lot shorter than you’d like. That’s because Wi-Fi signals are sensitive to interferences and obstacles.

While the new 6GHz band generally doesn’t suffer from interference other than when you use multiple broadcasters nearby, the other two bands have a host of things that can harm their ranges.

Also, note that the Wi-Fi ranges (and signal penetration) are generally the same on broadcasters of similar specs, a vary (model by model) only in sustained speeds and signal stability.

Common 2.4 GHz interference sources

- Other 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi broadcasters in the vicinity

- 2.4GHz cordless phones

- Fluorescent bulbs

- Bluetooth radios

- Microwave ovens

Common 5 GHz interference sources

- Other nearby 5GHz Wi-Fi broadcasters

- 5GHz cordless phones

- Radars

- Digital satellites

Obstacles and signal blockage

As for obstacles, walls are the most problematic since they are everywhere. Different types of walls block Wi-Fi signals differently, but no wall is good for Wi-Fi. Large objects, like big appliances, or elevators, are bad, too.

Here are my rough estimations of how much a wall blocks Wi-Fi signals — generally use the low number for the 2.4GHz and the high one for the 5GHz, add another 10%-15% to the 5GHz’s if you use the 6GHz band:

- A thin porous (wood, sheetrocks, drywall, etc.) wall: It’ll block between 10% to 30% of Wi-Fi signals — a router’s range will be that much shorter if you place it next to the wall.

- A thick porous wall: 20% to 40%

- A thin nonporous (concrete, metal, ceramic tile, brick with mortar, etc.) wall: 30% to 50%

- A thick nonporous wall: 50% to 90%.

Again, these numbers are just ballpark, but you can use them to have an idea of how far the signal will reach when you place a Wi-Fi broadcaster at a specific spot in your home. A simple rule is more walls equal worse coverage.

With the understanding of networking hardware above, let’s find out the best way to put them together. Again, a home network includes wired and wireless parts.

Best practice for a wired network

A single router (or gateway) is the only wired network you’d need with many homes. But if you have a larger home or one with multiple floors, it’s a good idea to think a bit bigger.

First and foremost, when possible, it’s best to run network cables around your home. In this case, pick a small room, or a closet, to serve as the IT room. Generally, this room is where the Internet service line enters the house.

From this room, run a network cable to each other room of the property where you intend to use a wired device (including a Wi-Fi broadcaster).

Note that you can’t split a network cable the way you do a phone line. The only way to turn one network cable into multiple ones is via a switch.

Extra: A home network’s hardware connection order

Note: This portion of extra content is also available in the post on Wi-Fi router setup and maintenance.

A typical home network diagram

Generally, in a home network, we have the following:

- The service line: That the line coming into the house from the street. It can be a phone line (DSL), a coaxial cable (Cable), or a fiberoptic line.

- The terminal device: This is the internet receiver. It’ll be a modem for a DSL or Cable broadband or an ONT for a Fiberoptic plan.

- The Wi-Fi router: The device that you need to set up.

- Optional devices: Patch panel, switches, mesh satellites.

Let’s use the arrow (➡) to represent a network cable and square brackets ([]) to describe optional devices. We have the following simple diagram:

Service line ➡ Terminal device ➡ Wi-Fi router ➡ [Switch] ➡ [patch panel] ➡Wired devices / [more switches] ➡ More wired devices.

A wired device can be anything that connects to a network via a network cable. Examples are a computer, a printer, Wi-Fi access points, etc.

For detailed steps on setting up a home Wi-Fi router, check out this post on the topic.

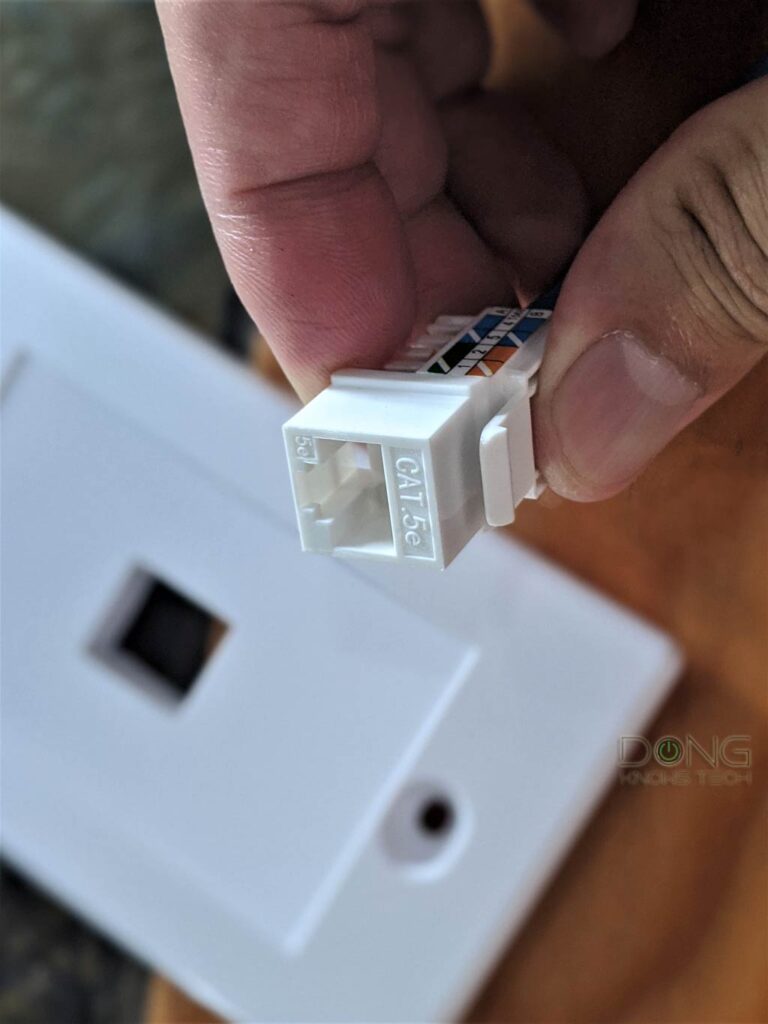

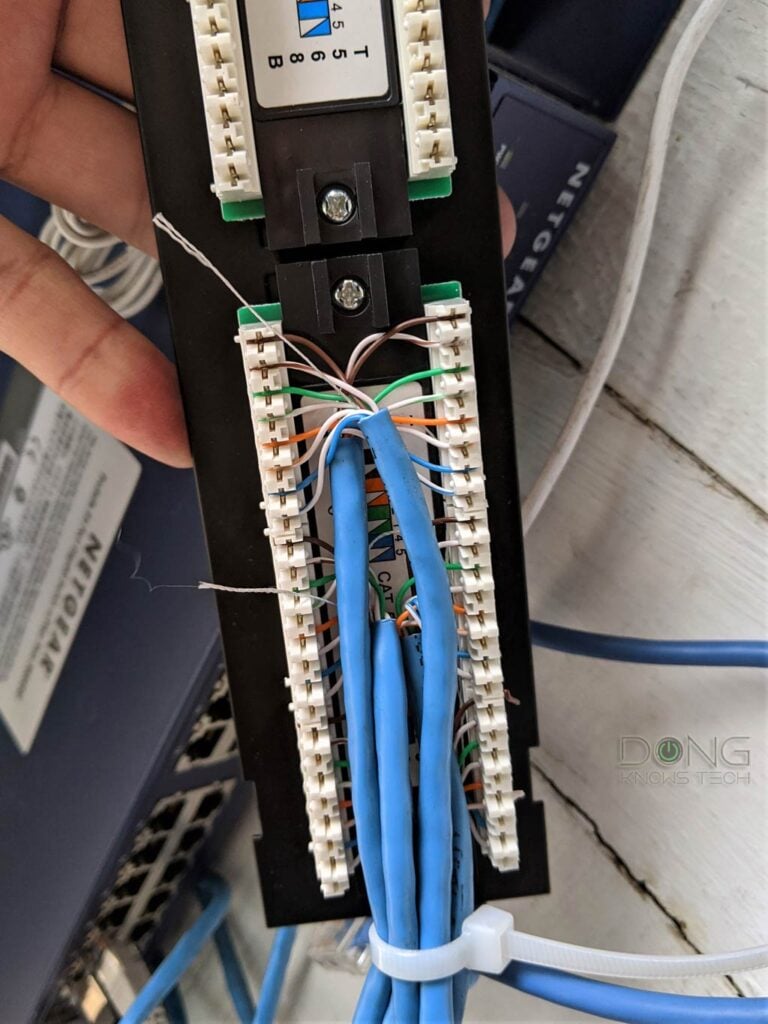

Get a patch panel

For better management, in the IT room, you should use a patch panel to organize all the terminals of the network cables that go to different places.

A patch panel is generally a collection of network ports, where each port is a keystone RJ45 jack that you punch down the wiring of a network cable’s end.

You’ll note that each port on the panel has a number. Now, at the other end of the cable, use another keystone RJ45 jack and mark it with the same number. Now you know which port goes to which room of your house.

Make sure you get a panel with enough room for all the cables you’ll use. A switch is also necessary if you run more cables than the number of ports on your router.

Of course, you can skip the panel and connect a cable directly into the router, but that’s a bit of a mess.

Best practice for a Wi-Fi network

Before you can have a Wi-Fi network, you must have a wired network, which might just be the router itself. After that, considering how Wi-Fi works, as mentioned above, the following are a few things you should do to get the best Wi-Fi experience.

1. Hardware placement

All home routers use omnidirectional antennas. As a result, wireless signals are broadcast outwardly as a sphere – more like a horizontal ellipse — with the router in the center. So if you place your router by the side of your home, half of its coverage will be on the outside.

Wi-Fi broadcaster placement: Dos

Here are the best places to put your Wi-Fi router.

- Center: As close to the center of the house as possible. Since, in most cases, the Internet drop is at a corner of a home, you can run a network cable from the modem to the router.

- High ground: It’s best to place your router above the ground. If you have a two- or three-story home, put the router on the second floor. If it’s a single-story home, place it on the ceiling or top of furniture, like a bookshelf.

- Out in the open: Avoid putting your router in a closet or behind a large, thick object — such as a TV or a refrigerator. Generally, you want to set the router in an open space.

- Vertical antenna position: That is if you want to signal to go out horizontally. Use the antennas in the horizontal position if you want the signal to go out like a vertical ellipse. Note, though, the antennas’ positions generally don’t matter much.

Wi-Fi broadcaster placement: Don’ts

Here are a few examples of where you shouldn’t place your Wi-F router:

- A closet

- Behind a large appliance like a fridge or a TV

- The laundry room

- A basement that has thick walls or below a thick concrete floor

Hardware placement for a mesh Wi-Fi system

A single router might not cut it in a large home, and you’ll need multiple broadcasters to form a Wi-Fi mesh system. Generally, a single router can cover about 1,800 ft² (170 m²). Each extender (or a mesh point) can extend another 1,500 ft² or so.

In this case, it’s best to use network cables to connect the hardware units. If that’s not possible, consider the following:

- Place the broadcasters of the systems at a good distance (not too far, not too close) one another. Generally, this distance should be about 30 ft (9 m) to 50 ft (13 m) if there’s a wall in between, or up to 75 ft (23 m) if there’s a line of sight.

- Minimize the number of walls or obstacles in between them.

- When there are two or more satellite units, place them around the main router to form a star topology — find out more on this post of mesh systems. You want to minimize the time signals have to hop before they get to the end device.

Note that a wireless mesh configuration is generally not good for real-time communication applications, such as gaming or video/audio conferencing. For that, you should consider getting your home wired or connecting the device via a network cable.

2. Get your own equipment

You generally have more control and a better network when using your modem and router instead of using equipment from your Internet provider.

If you use cable Internet, replacing the ISP-provided gateway with your own also saves you from paying the monthly rental fee.

3. Use network cables when possible

Again, when you need to extend your network, it’s best to run network cables to connect hardware units.

If you have a large home, consider using multiple hardware units connected to the main router via network cables to make sure you get the best coverage and the fastest speed.

When running network cables is not an option, you can try Powerline adapters that turn your home’s electrical wiring into network cables.

Note that a Powerline’s performance varies greatly depending on your home’s wiring and will not work with power strips or surge protectors. On top of that, they are generally much less reliable than network cables and unsuitable if you have high-speed Internet or intend to use Wi-Fi 6.

Final thoughts

Figuring out a home Wi-Fi network from scratch can be intimidating at first. Hopefully, that was only for you before this post. Like all things, home networking takes practice and some trial and error.

So get on it, and if you have more questions, the posts in the box below will help. There’s nothing more satisfying than being able to take full control of your home network.

[ad_2]

Source link